[Originally published on the Diversity, Equity & Inclusion website of Georgia State University at https://dei.gsu.edu/2021/12/doris-miller-pearl-harbor/ on Dec. 7, 2021.]

By Jeremy Craig, DEI Communications and Communications Manager, Office of the Provost

Dec. 7, 2021, marks the 80th anniversary of the attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor, the battle that led the United States to enter World War II against the Axis Powers.

As the nation marks this occasion, the DEI communications team looks back at the life and legacy of Doris “Dorie” Miller, a Black sailor in a segregated military who received the Navy Cross for his heroism on that awful day – and the influence he had for the years that followed.

From Texas to the Pacific

The son of a sharecropper, Miller was born on a 28-acre farm near Waco, Texas, in 1919. Looking to move beyond his hometown during the Great Depression, Miller attempted to enlist in the Army, but was turned away, and when he attempted to join the Civilian Conservation Corps of the New Deal, he was rejected. Eventually, he enlisted in the Navy in September 1939.

He trained in Norfolk, Va. as a mess attendant, during a time when institutionalized discrimination limited his options among different careers in the service. Under Naval regulations at the time, as a Black man, he was ineligible for promotion.

Eventually, Miller was assigned to the U.S.S. West Virginia, a battleship, in January 1940. Seen as “only” a lower-ranking enlisted Black sailor, his superiors likely did not know that his upbringing in Texas as an excellent marksman would prove to make a difference on one of the worst days of American history.

The Fateful Day

In the early morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Miller was below deck on the West Virginia, collecting laundry. When the surprise attack began, he reported quickly to his battle station – finding that the anti-aircraft gun had been destroyed.

During the chaos of the attack, Miller not only moved his captain away from a vulnerable part of the ship, but also manned other anti-aircraft guns despite having no training on those specific weapons. For 15 minutes, he fired at the Japanese aircraft until he had no more ammunition.

As the West Virginia sank, he pulled men to safety from oil-slicked water – some of it on fire, saving a number of lives. One of the last three men to abandon ship, he swam 400 yards amid enemy aircraft fire.

Persistence of Black Journalists in Telling the Story

While the Black press of the country was quick to recognize Miller’s heroism based on word of mouth that spread throughout the Black community, the Navy was not so eager.

In a list the Navy issued during the following January of those to be lauded for their bravery at Pearl Harbor, the Navy mentioned a Black sailor — Miller — without explicitly identifying him.

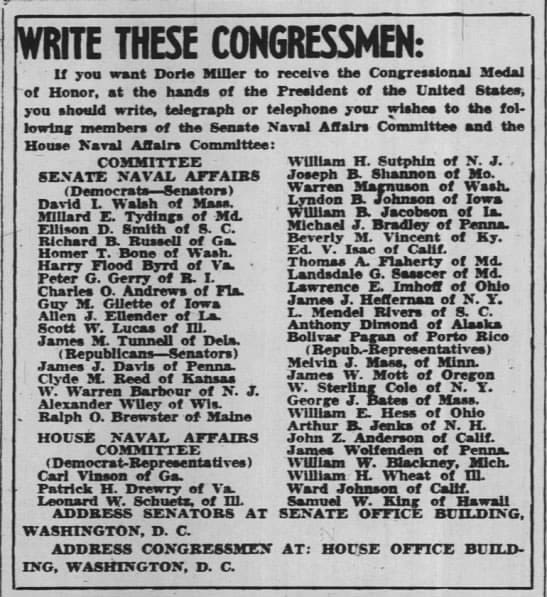

Black journalists – along with the NAACP and a bipartisan group of Northern politicians – pushed the Navy to honor Miller, eventually leading to President Roosevelt’s pressing of the secretary of the Navy to award the sailor for his heroic acts.

Recognition

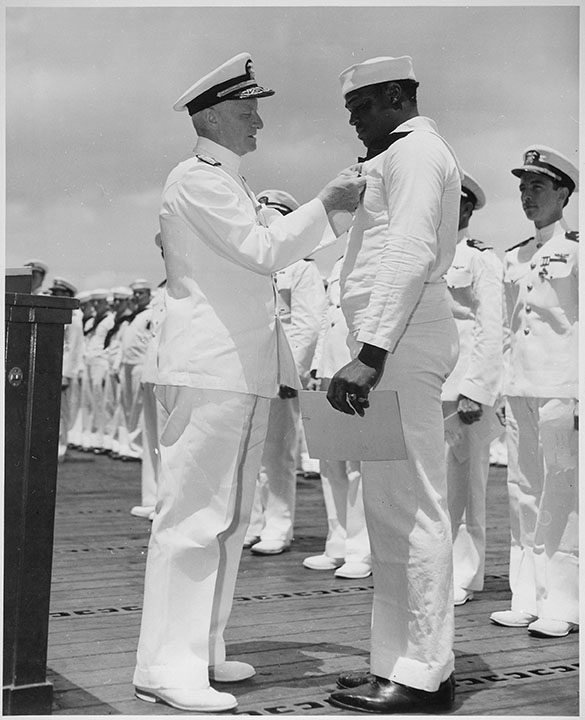

In May 1942, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz awarded Miller the Navy Cross.

The citation reads:

“For distinguished devotion to duty, extraordinary courage and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on December 7, 1941. While at the side of his Captain on the bridge, Miller, despite enemy strafing and bombing and in the face of a serious fire, assisted in moving his Captain, who had been mortally wounded, to a place of greater safety, and later manned and operated a machine gun directed at enemy Japanese attacking aircraft until ordered to leave the bridge.”

However, even this was not the same honor that might have been accorded to him — a Medal of Honor, the highest award the nation can give to a servicemember, following a request by a New York senator and Michigan congressman.

Patriotism and Equality

Still, Miller returned home to the mainland U.S. to publicize war bonds and to generate support for the U.S. war effort. The speeches increased his confidence and led to the bringing about of more opportunities and recognition of Black servicemembers.

His actions reinforced basic facts not recognized by American society: that Black servicemembers are patriots, capable to lead, serve others – and they, along with other Black Americans, are worthy of the full rights (including civil rights) that are due them. His actions also helped in the Black press’ “Double V” campaign – victory over tyranny and fascism abroad, and victory over discrimination at home.

Sadly, he would not live to see the fruits of what his heroism communicated to American society – an example that helped in the path toward integration of the military in 1948 and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. After his tour in the United States, Miller returned to active duty and was presumed killed in action at the Battle of Makin in the Pacific in November 1943, at the age of 22. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Honors on the Seas

The U.S.S. Doris Miller (CVN-81), a Ford-class supercarrier, is under construction in Newport News, Va. and will be commissioned in 2032. It is the second vessel to bear his name.

The Ford-class is the Navy’s newest generation of aircraft carriers, and the vessel will be one of five ships in this class, which include the Gerald R. Ford, the John F. Kennedy, the next U.S. naval vessel to be named U.S.S. Enterprise, and another carrier as yet to be named.

It will also be the first aircraft carrier to be named in honor of a sailor for actions while serving as an enlisted servicemember in the U.S. Navy.

The first ship named for Miller (U.S.S. Miller, FF-1091) was a destroyer escort ship commissioned in 1973. A Knox-class ship, it served in the Atlantic Fleet. The Miller was decommissioned in 1991.

Sources

“Cook Third Class Doris Miller’s Navy Cross Citation.” (Jan. 15, 2020). Naval History and Heritage Command, United States Navy. Retrieved from the Internet Archive on Dec. 7, 2021 at http://web.archive.org/web/20210321072019/https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/diversity/african-americans/miller/doris-millers-navy-cross-citation.html.

MILLER (FF 1091), (2006). Naval Register, U.S. Navy. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2021 from https://www.nvr.navy.mil/SHIPDETAILS/SHIPSDETAIL_FF_1091.HTML. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20220507172428/https://www.nvr.navy.mil/SHIPDETAILS/SHIPSDETAIL_FF_1091.HTML.

“Navy Names Future Aircraft Carrier Doris Miller During MLK, Jr. Day Ceremony” (Jan. 20, 2020). Office of the Secretary, United States Navy. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2021 from https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Press-Releases/display-pressreleases/Article/2236587/navy-names-future-aircraft-carrier-doris-miller-during-mlk-jr-day-ceremony/. Archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20211207144237/https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Press-Releases/display-pressreleases/Article/2236587/navy-names-future-aircraft-carrier-doris-miller-during-mlk-jr-day-ceremony/.

Official Military Personnel File for Doris Miller: Documents, correspondence, decorations, awards and commendations, 1939-1974. Department of the Navy. Retrieved from the National Archives and Records Administration on Dec. 7, 2021 at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/74876313.

Smith, D. (2021). “Illuminating a Giant.” Baylor Magazine, Spring 2021. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2021 from https://www.baylor.edu/alumni/magazine/1903/index.php?id=976949. Archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20211207154725/https://www.baylor.edu/alumni/magazine/1903/index.php?id=976949.

Tucker, E. (Dec. 6, 2021). “A Black Sailor’s Heroism at Pearl Harbor.” Teaching American History. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2021 from https://teachingamericanhistory.org/blog/a-black-sailors-heroism-at-pearl-harbor/. Archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20211207143225/https://teachingamericanhistory.org/blog/a-black-sailors-heroism-at-pearl-harbor/.

Tucker, G. (Dec. 3, 1995). “Navy Hero Served With Valour, Despite Name.” The Virginian-Pilot, Page J-3, Sunday, Dec. 3, 1995. Retrieved online Dec. 7, 2021 from https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1995/vp951203/12010491.htm. Archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20211207153031/https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1995/vp951203/12010491.htm.

“Write These Congressmen,” The Pittsburgh Courier, April 4, 1942. Retrieved Dec. 7, 2021 from https://www.newspapers.com/clip/17268828/write-these-congressmen/. Archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20211207143640/https://www.newspapers.com/clip/17268828/write-these-congressmen/.