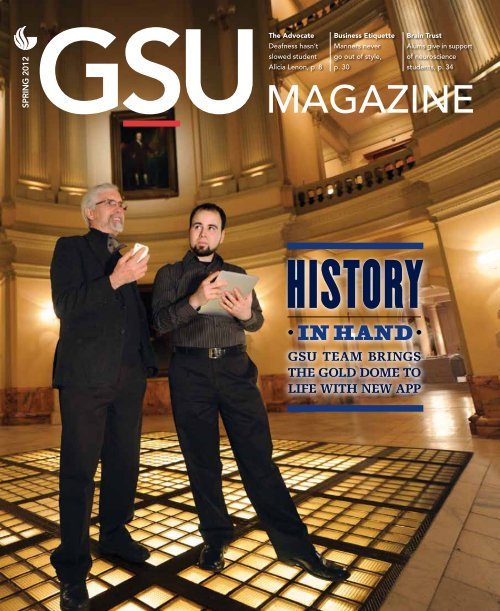

GSU team brings the Gold Dome to life with new app

From the Spring 2012 issue of GSU Magazine; original article archived at the Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20130104002344/http://www.gsu.edu/magazine/2012spring/769.html

For more than a century, the wood and marble halls of Georgia’s state Capitol building have thrummed with legislators and leaders, lobbyists and citizens, all with the aim of shaping Peach State policy.

In a state that has undergone massive political and societal changes in its long history, the grand old edifice in downtown Atlanta stands not just as the working center of government for the economic powerhouse of the Southeast, but as a symbol of Georgia’s rich past.

Many visitors to the Capitol aren’t aware of all the history that runs deep through the stately building. Learning about this past can help them understand Georgia’s present, and maybe even its future.

Professor of history Tim Crimmins and Chris Escobar, a graduate student in the Department of Communications’ moving image studies program, have created a way to make the history of the Capitol come alive for its visitors – all at the tap of an iPhone.

Now available for free from the Apple iTunes App Store is the Georgia Capitol Tour, an application for the iPhone, iPod Touch and iPad full of multimedia content – photos and videos of state governors, legislators, leaders, activists and even a former U.S. President – that gives visitors a handheld Capitol tour.

“This place has incredible power,” says Crimmins, director of the GSU Center for Neighborhood and Metropolitan Studies. “But what happens with many people is that they go to places and they have no way of connecting where they are with the past.”

With the new app, people will get that connection in a dynamic and engaging way, Escobar says.

“Part of the fascination with this is that you can learn in a way that appeals to you, and learn it at your own pace,” he says. “You can create the storyline for yourself. The experience is not the same for everyone, and because it can be catered to you by your own choosing, it makes it interesting and becomes a new component to learning old things.”

A Partnership Begins

The partnership between Crimmins and Escobar began during Escobar’s freshman year, when he enrolled in one of GSU’s Freshmen Learning Communities (FLC) – a program whereby incoming freshmen in groups of 25 all take the same classes centered around a particular theme. Escobar’s choice of FLC – themed “filming the metropolis” – was led by Crimmins.

In the FLC, Crimmins taught a class on the historical perspectives of global cities using media ranging from video games to German expressionist films.

“Even though Crimmins is a history professor, he very much embraces media and new technology; new ways of teaching old things,” Escobar says. “His way of teaching sparked my interest.”

Escobar excelled in the class, and Crimmins arranged for him to become an assistant. Escobar managed projects for the professor in subsequent classes until he graduated in 2008. After earning his degree in communications with an emphasis in film and video, Escobar enrolled in the master’s program in moving image studies with a concentration in production.

“As a freshman, he really impressed me,” Crimmins says. “He graduated, came back, and I was really happy to see him in the graduate program.”

In 2007, Crimmins and Georgia state Capitol historian Anne Farrisee published “Democracy Restored: A History of the Georgia State Capitol” (University of Georgia Press, 2007), a 190-page illustrated history of the Capitol for which Crimmins was named Georgia Author of the Year in history by the Georgia Writers Association.

Crimmins, who had chaired the Commission on the Preservation of the Georgia Capitol starting in the mid-1990s, wanted to have snippets of information from the book available to visitors to the Capitol. Initially, he thought about kiosks with visual displays, but he soon dismissed that idea.

Having overseen a decade-long historical facelift the Gold Dome, he didn’t want anything that would, he says, “intrude in on the place we had restored.”

He went on to consider technologies for a digital tour, such as a “wand” or other devices sometimes used for museum exhibits. He received a grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities to further explore these possibilities.

That’s when Crimmins reached out to his tech-savvy former student. And Escobar immediately thought of the technology behind his iPod Touch.

“The idea came as the evolution of the personal audio tours,” Escobar says, “but rather than use random technology, we wanted to use one that so many people have and one that is proven.”

By creating an application using this technology, they could create the tour for a fraction of the cost, and better yet, would have complete control over the content.

From there, they spent months collecting video from archives, researching, designing and interviewing both historians and people who had first-hand accounts to tell.

“You meet all of these interesting people, so it doesn’t become faceless history,” Escobar says. “And that’s the neat thing about this project.”

One of the major threads of state history that Crimmins and Escobar are retelling, partly through recollections from people who were there, is that of desegregation at the Capitol – and in the state.

“What surprises me is the tenacity you can say that some of the people had back then, like with Lester Maddox,” Escobar says. “There’s the fact about how he became famous by threatening black citizens not just by physically pushing them out, but by also threatening them with a gun.

“That kind of bold-faced racism blows my mind, but it was also met with calm, patient wisdom that had a perspective before its time,” he says.

Marking Change

On Jan. 12, 1971, a young incoming governor named Jimmy Carter stood in front of the Capitol and issued his inaugural address. In it, he uttered a simple phrase that helped to mark the end of official state-sponsored discrimination in Georgia.

“I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over,” said Carter, who in 1976 would be elected president of the United States. “No poor, rural, weak or black person should ever have to bear the additional burden of being deprived of the opportunity of an education, a job or simple justice.”

Nearly 40 years later on a cold December day in 2010, former President Carter came back to the Capitol to reflect on those words for the project.

“It got a lot of attention outside of the state as well, and within a couple of weeks, because of that speech, I was on the cover of Time magazine,” Carter says in his filmed interview. “But what I said was accepted … by what I would say was almost complete equanimity by the people of Georgia, because they were ready for an end to racial segregation.”

In 1962, just a year after Carter had first arrived at the Gold Dome as a state senator, Atlanta attorney Leroy Johnson won a state senate seat, becoming the first African-American to be elected to the Georgia General Assembly since the end of the Reconstruction era.

At first, the majority of his fellow senators didn’t even acknowledge him in the hallways.

“I would walk down the corridors of the state Capitol, and I would say ‘good morning,” Johnson says, remembering that oftentimes the response would be a dismissive grunt.Â

But he persevered. He soon learned the power of his vote and how things work in the state legislature. Once, while serving on the education committee, he came upon a tie vote on a piece of legislation.

“When I walked into the door, they didn’t see the black senator to whom they had not spoken to at all that day; they saw a vote,” Johnson says. “A vote that could send their bill out of the committee, or one that would kill that bill. And they forgot about how black I was for a split moment to get my vote, and I knew then that’s how powerful the vote was.”

His legacy remains in the state Capitol, and in 1996 his portrait joined those of former governors, Martin Luther King Jr., and other notable Georgians, on the third floor.

“Although Leroy Johnson was not an avid and in-your-face civil rights activist, his quiet demeanor and his scholarly and legalistic approach showed all of us that he was a man of substance,” Carter recalls. “And we soon forgot about what race he was.”

A Technological Boost

Lonnie King, now a doctoral student and history instructor at GSU, tells the story of the 1960 march to the Capitol to protest segregation in Georgia schools in an app video.

In 1960, Lonnie King and his compatriots in the Atlanta Student Movement issued a bold call for full civil rights for African-Americans and led sit-ins across the city in non-violent protest of segregation.

On May 17 of that year, King and his fellow students marched to the state Capitol to commemorate the sixth anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that public school segregation was unconstitutional.

They were faced with derision and were confronted by a large group of angry counter-protesters.

Fifty years later, King recounted that experience to Crimmins on the Capitol grounds.

“The world was beginning to change in 1960, and a lot of folks who were in power at the Capitol, like Governor [Ernest] Vandiver and others, I think did not feel the earthquake that was shifting under their feet,” King recalls. “Their response to the challenges to the old system was to bring out the billy clubs, the state troopers and to surround the Capitol with them.”

Then as now, when people can send messages that magnify causes with a few taps of a mobile device, it was modern technology – in this case the relatively new medium of television – that helped the Atlanta Student Movement’s impact become larger in the national consciousness.

“The press and television were able to come in, to show on the nightly news these atrocities that were being committed on these college kids,” King says. “I think, in a way, that was the thing that tipped public opinion, of course along with the eloquent speeches of Martin Luther King Jr.”

And what might have happened if today’s iPhones, Twitter and text messaging had been available?

“We would have gained even more rights,” King reflects. “And if they had not have had TV, we wouldn’t have gotten the success that we got.”

King, now a doctoral student who teaches history at Georgia State, hopes the new Capitol history application helps speak to today’s students in an accessible medium.

“It’s a medium that is very foreign to a lot of us who are over 70 years of age, but it’s like a piece of cake for people under 40,” he says. “And I think those are the people who need to have a better understanding of what happened.”